"Never Better"

How saying "yes" 32 years ago led to a lifetime of experiences and memories

The following is a reflection on an influential relationship, cut too short 20 years ago this week, and how that connection impacted my professional life.

In hindsight, I had no idea to what I was saying “yes” in late July 1990. It was impossible to foresee how that simple word would set me on a course of events that would take me to 10 countries, set in motion the ability for me to work two Olympic Games, and, most importantly, create lifelong friendships, one of which I celebrate in memoriam today.

Before I get to the question which led to the “yes,” let’s first set the scene. I was a junior at Drake University in the spring of 1990, working in the sports information department with our director, Mike Mahon, a member of the CoSIDA Hall of Fame. Mike had some connections with the U.S. Olympic Committee. On a bit of a lark, I applied for, and received, an internship in the USOC Media Relations office in Colorado Springs. I was 21 years old with no iPhone, no email, a few maps from AAA, and a general idea of where I was going, but no idea where I was headed.

When the semester ended, I loaded some essential belongings into my 1980s Toyota Corolla and drove west along I-80 through the burgeoning cornfields of western Nebraska to I-76, spending an uneventful evening dining alone in North Platte. I encountered the Rocky Mountains for the first time and, once I hit Denver, I turned south on I-25 toward Pikes Peak and the U.S. Olympic Training Center. It was here my journey began, living in the barracks, eating shoulder-to-shoulder with elite athletes in the dining hall (Christian Laettner once memorably announced to no one in particular but to anyone within earshot how much he enjoyed fish sticks), and netting $4 per day after room and board were deducted. It was, honestly, an amazing experience for a wide-eyed 21-year-old.

I was welcomed by a legendary media relations staff directed by the late Mike Moran, whose deep voice and imposing physical presence immediately filled any room in which he entered. Gayle Petty, Bob Condron (CoSIDA HOF), Jeff Cravens, and Barbara Gresham completed my list of impressive colleagues. From this esteemed group, I learned how to promote Olympic sports, the value of receptions known as “per diem stretcher extraordinaires,” and what the heck the U.S. Olympic Festival was. For the record, it was a multi-sport, Olympic-style event featuring the best amateur athletes from the United States competing on creatively titled teams, North, South, East and West.

In 1990, the Festival was to be held in my hometown of Minneapolis-St. Paul. Gayle assured me it was highly unusual to have an intern work at an event. Typically, the interns (there were four of us) stayed in the central office to answer phones and conduct research. But, Gayle reasoned, there might be value in having my local knowledge on the ground during the Festival, scheduled for the middle two weeks of July 1990. So it was decided my internship would end there, on or about July 16.

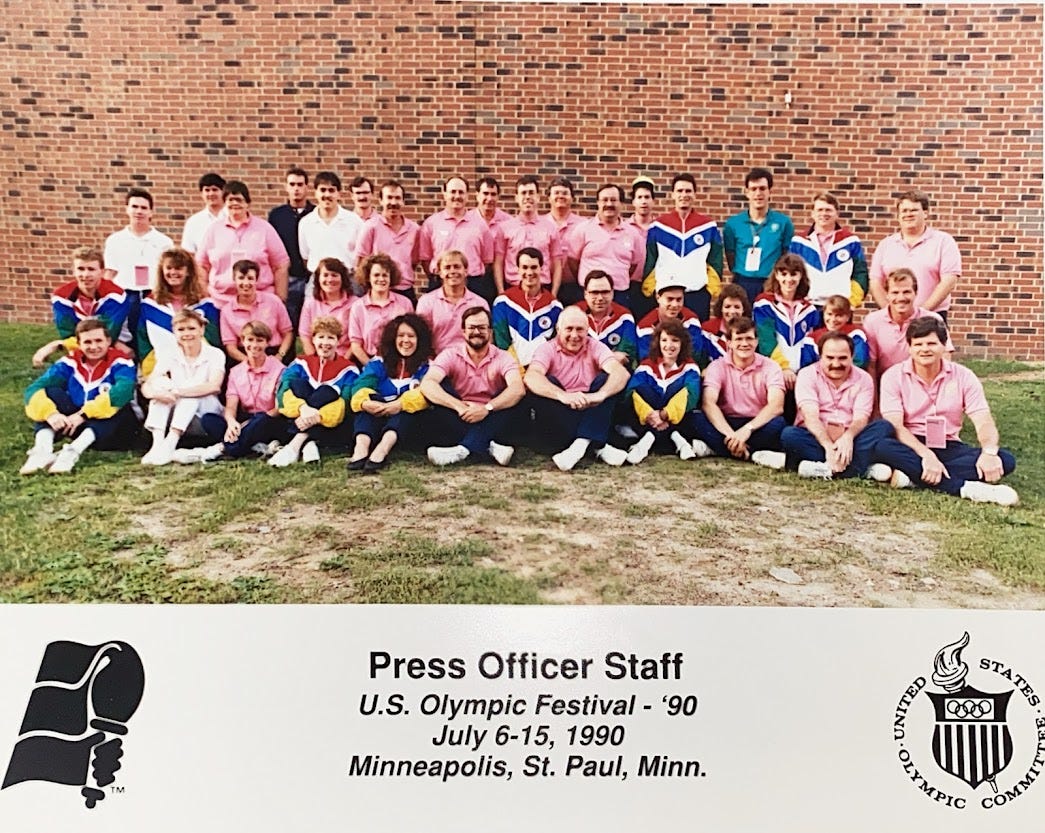

While the rest of my colleagues boarded planes to the Twin Cities, I re-loaded the Corolla and headed east through Nebraska where the corn had grown taller (knee high by the Fourth of July) and into Minneapolis. During multi-sport events such as the Festival, the USOC supplements its media staff with “press officers.” These are typically sports information directors who get permission to spend a fortnight in a hotel serving as a media liaison for sports such as team handball, archery, and taekwondo. Several iconic SIDs were on the 1990 staff, including people with whom I still share a connection today, names such as Paul Allan (CoSIDA HOF), Frank Zang, Jan Miller Martin, Dave Lohse (CoSIDA HOF), Rich Wanninger, and many more.

My mentor from Drake, Mike Mahon, was also there. And that is where this story takes a turn into the unknown with that fateful word, “yes.”

Our previous assistant SID at Drake was Helen Strus, who had left to take a job in press operations with the organizing committee of the 1990 Goodwill Games in Seattle which were to begin July 20, a few days after the Festival began. Born in 1986 in St. Petersburg, Soviet Union, these Cold War multi-sport games were the brainchild of Ted Turner, designed to provide content to his emerging TBS superstation while simultaneously enabling athletes from two superpowers (and other nations) to compete against one another.

Helen had phoned Mike Mahon in a panic. Someone they had hired to work during the Games had unexpectedly canceled. She was hoping Mahon could fly to Seattle to help out, but Mahon could not be away for another two weeks. I had worked briefly with Helen, and he suggested me, knowing my internship was ending and I had no other summer plans. She asked, and I said “yes.”

And so, the day after my USOC internship ended, I boarded a non-stop Northwest Airlines flight from Minneapolis to Seattle where I would assist in whatever odd press operations roles were needed for 10 days. I would return home prior to the Games’ conclusion. I settled in, helping Helen and Carrie Devine in the Main Press Center, and learning a lot. (Helen is now the long-serving director of marketing and communications at MetLife Stadium. Carrie now owns Gifted Boston, a boutique store in Boston’s South End, after serving as a national advance lead for President Barack Obama.)

One day, Helen and Carrie were not there.

The organization for which they worked, International Event Management, was concerned about payment and pulled their press operations employees off the job. I was a 21-year-old who had naively agreed to work for the cost of an airline ticket and accommodations. I was not drawing a per diem or salary. So, I showed up for work.

I remember calling Mike Moran and Jeff Cravens at the USOC (they were not involved in the event) and telling Mike, “I think I am running the Main Press Center now.” Moran laughed. The prospect of a college junior running the Main Press Center at a major multi-sport international event is as ludicrous now as it was 32 years ago.

And that is how I met Rich Perelman and Bruce Dworshak. The local organizing committee had contracted with Rich, fresh off a highly efficient and successful media operations enterprise at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games, to help sort out operations in the absence of staff while competitions were taking place.

I recall meeting across a folding table with Rich, a colorful, business-like lawyer with round dark-rimmed glasses, and explaining who I was, how I got there, and what I had been doing in the MPC. I imagine I was nervous, but that memory is not clear. I offered to stay past my appointment until the end of the Games because, really, I had nowhere to be until the fall semester began. But I needed some things. I needed time off to do laundry. I needed my hotel room extended. And, I wanted to be paid. How much, he asked? How much?!? How the heck did I know? I was a college kid. So, I told him I wanted $35 per day as that was the per diem the press officers received at the Festival I had recently left. Rich agreed, although he later told me I should have asked for more, and had me a sign a contract.

I was now reporting to Bruce Dworshak who had assumed the job of running the MPC. Bruce was a tall, thin, bearded gentleman racing against time to keep a full head of hair. A native of Oregon, he was a Duck through and through, and would gladly recite the fight song on command. He was full of endearing quirks, such as wanting papers stapled together in a precise way, in the upper left-hand corner at a 45-degree angle. He was eternally optimistic, responding to anyone who asked how he was with his signature declaration, “Never better!” I find myself using that phrase as part of my normal lexicon when asked the same question.

Helen and Carrie both eventually returned to work and the Goodwill Games ended without further incident. I headed back home for a brief visit, before returning to Drake, uncertain of the future. I would keep my network and contacts, working the 1991 Festival in Los Angeles and the 1992 Olympic team processing in Tampa, while working on a master’s degree at Drake. From late 1992 to May 1995 I worked with USA Wrestling as public relations manager before reuniting with Bruce as part of the press operations team in Atlanta for the 1996 Olympic Games.

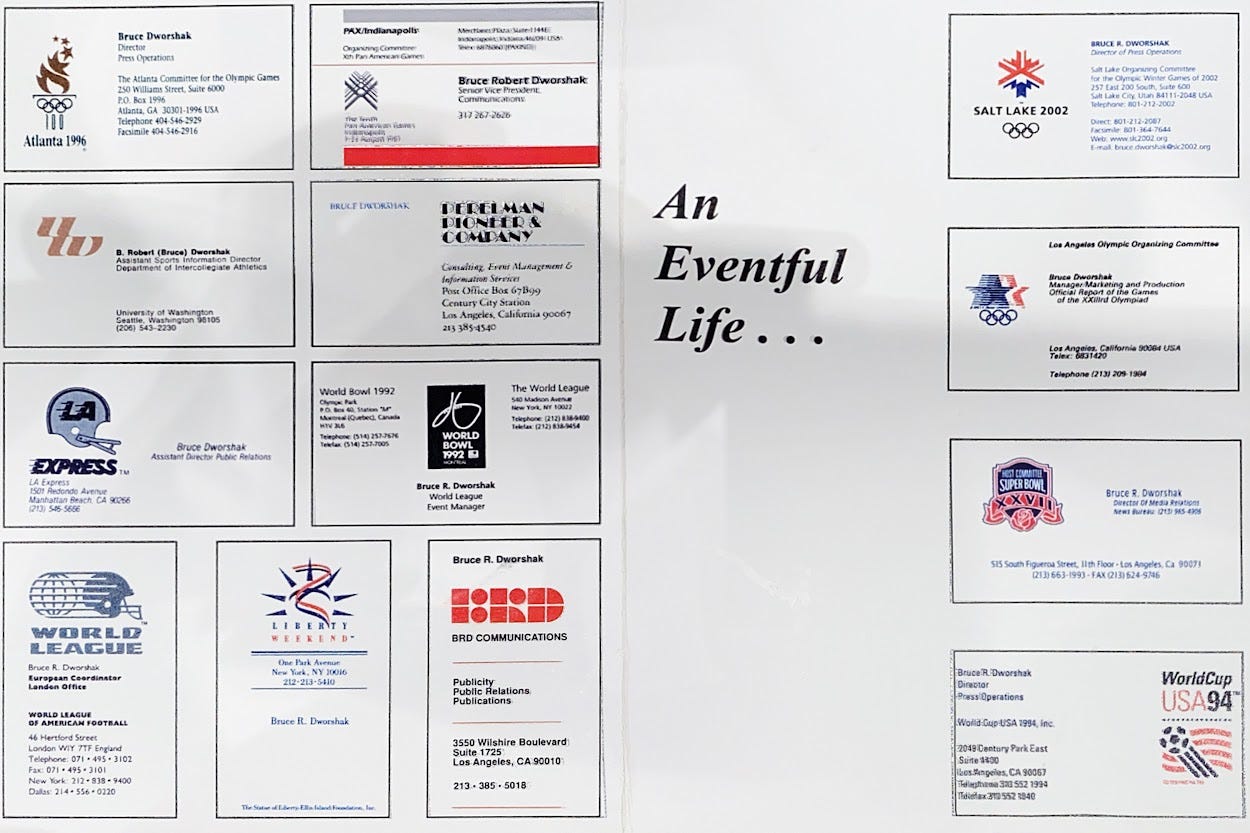

Bruce brought a wealth of experience to Atlanta, having worked with the 1984 Olympics, 1994 FIFA World Cup, Super Bowl XXVII, and a host of other events. Jennifer Jordan, with whom I had worked in Seattle, would be my boss. It was a mini Seattle reunion. I recall approaching Bruce about taking a graduate class in spring 1996 at Georgia State University to satisfy the last remaining credits needed for my masters degree. My five-year clock to complete the degree was running out, but I was worried about the workload in the final months prior to the opening of the Games and whether I could effectively do my job. Bruce encouraged me to take the class, saying I would never know when I would need the degree. Indeed, without that degree, I would have never been in a position to get a PhD.

Unfortunately, the communications leaders in Atlanta did not fully understand and appreciate the role of press operations and, several months prior to the Games, Bruce departed the organizing committee, but I stayed, believing in what Bruce was building. The 1996 Games experienced several operational hiccups, some of which could have been avoided, I think, if Bruce had stayed in his role.

In March 1999 a position opened for manager, venue press services at the Salt Lake Organizing Committee, working under the director of press operations, Bruce Dworshak. I called and left a message. He called me back enthusiastically. I flew out to interview and in May, we moved to Salt Lake City where I would once again work with Bruce, Rich Perelman, Frank Zang, Carrie Devine and many others.

Bruce and I were both morning people, and we both lived downtown Salt Lake. Eventually we started riding to work together, Bruce picking me up in the SLOC-issued Astro van made by Chevrolet. It was a boxy, slow-moving, but functional, vehicle. We believed we could encourage its acceleration by commanding, “Astro van, launch!” as it was shifted into drive. If a less fun car exists, I am not sure what it is.

I recall our short rides to work, listening to NPR’s Morning Edition. We talked about world events, the Dodgers, and college football. On September 11, 2001, we were both in our cubicle offices in downtown Salt Lake just before 7:00 am mountain time. Bruce was talking via phone to the International Olympic Committee’s press operations coordinator when suddenly the phone line went dead. We soon learned why and both gathered around a television set to watch the tragic events unfold until our CEO, Mitt Romney, sent all of us home.

The 2002 Olympic Games and Paralympic Games both went off smoothly with none of the missteps we experienced in Atlanta. I like to think Bruce’s leadership had something to do with that, at least in our area of press operations.

Even as the planning for the Games was fully underway in 2001, we were already thinking about the next thing. I wanted to get a PhD and become a professor. Bruce graciously wrote letters of recommendations to universities on my behalf, once again influencing my education. His encouragement of my own professional goals and development is something I endeavor to apply with staff I oversee in my current administrative role today. Bruce was going to Korea to assist with the 2002 FIFA World Cup.

Unfortunately, Bruce never made it to Korea. Twenty years ago this week, on April 9, 2002, Bruce passed away at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in his hometown Los Angeles at age 48, just more than a month after the Olympic Games ended.

That his death warranted a story in the Salt Lake Tribune, Los Angeles Times, Deseret News, and other media outlets was appropriate, though he would have certainly been embarrassed by the attention. He did not seek media coverage. He was not a public relations person. He was an operations person, focused on making as easy as possible the media’s job of covering Olympic athletes. I still use the lessons he taught me, and the experiences he gave me, as examples in my sport media and public relations class. Twenty years later, the fundamentals of what we provided in 2002 are still at the core of how proper media operations should be executed.

A few days after his death, many of us attended a memorial/celebration of Bruce’s life at All Saints Church in Pasadena on April 13, 2002. The organizing committee presented to Bruce’s family a mounted torch similar to the ones used during the Olympic torch relay. As we discussed how we wanted to inscribe the plaque on which the torch was mounted, I suggested the words made famous by Jackie Robinson decades earlier.

“A life is not important except in the impact it has on other lives.”

Rich Perelman recently sent an email to a group of three dozen or so individuals whose lives had intersected at some point with Bruce. To a person, everyone shared recollections of a life well-lived. It was wonderful to read the tributes.

Bruce hired me to work two Olympic Games, experiences I will never forget. But more importantly, it was Bruce’s character and desire to make everyone around him grow and excel in their jobs and their lives that touched me most. He had a big heart. Even in his death, Bruce Dworshak is still impacting other lives. RIP, my friend.

“Astro van, launch!”

The Bruce Dworshak Memorial Scholarship was established in his name at the University of Oregon School of Journalism and Communication, from which he graduated in 1975. The fund has reached more than $70,000 to date.

I know, I did. So funny. Such life-long friends in that picture. How did we ever get so lucky?

This is spectacular, Steve. Bruce influenced so many of us and profoundly impacted the world of press operations. How blessed we are that you said, “Yes.”Dear God I remember those Astro vans!