It was right around this time of year, 26 years ago, when I was working in public relations for Koch Refining Company in Rosemount, Minn. Yes, that Koch. I was still in my 20s and about to experience what every public relations person dreads, a Sunday exposé that carries tremendous reputational damage to my employer.

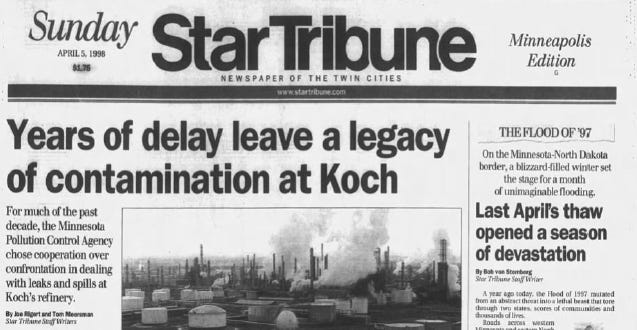

We spent hours answering the reporters' detailed questions, and twice that amount of time preparing to meet with the reporters for our on-the-record conversation. When the story was published, occupying countless column inches in the Sunday, April 5, 1998 Minneapolis Star Tribune, perhaps two paragraphs were attributed to our side of the story.

The thing was, the reporters had it correct. Two months earlier, two employees filed a whistleblower lawsuit alleging pollution violations. The company was responsible for contributing to groundwater contamination. Two days before the Sunday exposé, the company had agreed to pay a record $6.9 million fine to the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. As the refinery’s spokesperson, my name is forever associated in the public record with the incident. My friends renamed my fantasy football team the Black Goo as a tribute.

What I learned from that experience confirmed what I had learned as an aspiring journalism student in college: professional, investigative journalists are really good at their job. They do the research. They triangulate with sources. They find things companies and/or individuals would prefer the public not know. Chances are good if they come to you with questions, they have… something.

This went through my mind as I watched LSU women’s basketball coach Kim Mulkey’s anger-filled rant today about a forthcoming Washington Post story about… something. That something cannot be positive for Mulkey. But I am willing to bet that something is not “fake news.” Mulkey has threatened to sue for defamation if the WaPo publishes a false statement, which sport lawyer Darren Heitner quickly pointed out is a high bar to clear. As did Michael McCann in Sportico.

Many others have pointed out the hypocrisies in Mulkey’s statement, which is transcribed here by On3. She acknowledged she has known the reporter was working on the story for two years, but expressed outrage that he would demand a response now. Two days before the NCAA tournament.

“After two years of trying to get me to sit with him for an interview, he contacts LSU on Tuesday as we were getting ready for the first round game of this tournament with more than a dozen questions, demanding a response by Thursday right before we’re scheduled to tip-off. Are you kidding me?”

Reporters file their stories when their editors say they are ready, not when it is convenient for the subject. Like many, I question why she has not engaged with the reporter over the past two years. Did she think ignoring the story would help it go away?

Why she felt reading this statement with such emphasis was a good idea is a mystery. Did the LSU communications staff encourage it? What about the AD? Or, did she go rogue and say, “screw it. I am doing it my way.” Instead of helping her cause, all this did is bring attention to the story in which so many people are now suddenly interested. It was not an effective public relations strategy.

Mulkey’s rant occurred less than 24 hours after SI columnist Pat Forde reported about a forthcoming story, suggesting wagons were “being circled.” That Tweet prompted enough questions to inspire Mulkey to voice a three-plus-minute soliloquy on how bad journalists are, echoing much of the divisive rhetoric employed a segment of American society that believes journalists are inherently bad. Unless they are saying nice things about you.

“But you see, reporters who give a megaphone to a one-sided, embellished version of things aren’t trying to tell the truth. They’re trying to sell newspapers and feed the click machine. This is exactly why people don’t trust journalists and the media anymore. It’s these kinds of sleazy tactics and hatchet jobs that people are just tired of.”

This whole episode is emblematic of a larger challenge in communication. Organizations can control their message. They don’t need the media to carry those messages to their stakeholders. Individuals and organizations suggest if the news about them is not positive, then it must be false. There must be some sort of agenda. It must be fake.

I don’t blame organizations for wanting to promote good stories and minimize the negative ones. Or, at the very least, ensure the organization's message is part of the story. That is a PR person’s job. That was my job.

But a good investigative reporter views their job as making sense out of complex, contextual situations. This means presenting the good, and the bad, about an organization or individual. This involves reporting both sides of a story. If the reporter were not seeking Mulkey’s reaction for the past two years, it would be a hatchet job.

Instead, it is likely a professional journalist engaged in good reporting which, likely, happens to be unflattering and embarrassing to a public figure. Individuals and organizations who choose to battle publicly with the media rarely wind up being viewed in a positive light.

I guarantee you she went rogue. She does what she wants and answers to no one. Not even her AD. 🥴