Fifty years after NCAA realignment, the talking points are still the same

A look back at the last major transformational moment in NCAA Governance

Note: This post originally appeared at Extra Points with Matt Brown, Monday, September 18, 2023.

--

The masthead of the August 15, 1973 NCAA News ran not across the top of the page, but below the double-stacked headline, “Six Senators Seek Federal Control of High School and College Athletics.” This old publishing trick, placing one article above the masthead while another runs below it, was a technique to give two stories similar treatments.

As fascinating as it was to read the article about government involvement in sports and consider the irony that here we are, 50 years later, with Congress once again taking an interest in college athletics (I will take a deeper look into that soon enough), that was not the reason for my dive into the archives.

What I was seeking was context regarding the NCAA membership vote 50 years ago, on August 6, 1973 at the Hyatt Regency O’Hare in Chicago, that divided the organization into three Divisions. At the time, competition in many sports was split into “University” and “College” Divisions. For example, the 1972 University basketball title went to UCLA, led by Bill Walton. The Bruins defeated Florida State, 81-76. That same year, the College Division title was won by Roanoke, which downed Akron, 84-72. Fifty years later, Roanoke and Akron sponsor dramatically different athletic programs.

I wanted to know what athletic administrators were saying a half century ago regarding the need for this change, and how has that evolved? It is important to remember the NCAA did not officially begin sponsoring championships for women’s sports for another decade, so all of the conversation leading up to the vote centered around men’s sports.

The formation of the first Special Committee on Reorganization occurred at the NCAA’s convention in August 1971 held in San Francisco. It barely registered in the NCAA News, lumped together with news of other committee formations and the names of individuals filling vacancies. The seven-member committee was chaired by David Swank, a law professor and faculty athletic representative from the University of Oklahoma, and presented with the charge of studying “the Association’s long-range and administrative roles in intercollegiate athletics and to give immediate attention to possible legislative reorganization of the NCAA.”

The Special Committee presented its final report to the NCAA Council in August 1972. The August 15, 1972 NCAA News, as it usually did, covered the topics it felt were of importance to the association. Admittedly, the NCAA News functioned as a classic house organ, so we would expect its coverage to highlight comments which reinforce organization views. Important topics in August 1972 included construction of a new office building in Mission, Kan. and the news that the NCAA had sold out its advertising inventory for the upcoming monopoly football broadcast schedule on ABC television. Reorganization did not rate as a significant enough issue to warrant a headline.

In fact, the banner headline in that issue highlighted Big Ten Commissioner Wayne Duke’s speech at the CoSIDA Convention in which he said, “The purpose of collegiate athletics is more than winning, entertainment and the dollar sign. We’re in the education business.” When in doubt, pivot to the organization’s talking points.

Following the association’s August meeting in Boston, a three-part series on the reorganization proposal, as recommended by the NCAA Council, began with the October 15, 1972 issue of the NCAA News. This early iteration called for reorganization into Division I and Division II, noting the Council favored the simplicity of two Divisions, as opposed to three which had been discussed.

“An institution which cannot (or chooses not) to meet the new requirements of Division I membership and joins Division II then may select two sports in which it wishes to compete in Division I championships,” read the unbylined article.

Membership in Division I would require each institution to possess “a broad range of sports sponsorship and a “major” program in at least two sports, at least one of which must be football or basketball.” Additional sports identified as “major” included baseball, ice hockey, lacrosse, soccer, volleyball, or water polo.

The remnants of this proposal can be seen most prominently in ice hockey and lacrosse where Division III schools such RPI, Clarkson, and Johns Hopkins field competitive Division I programs.

Division I institutions must “sponsor a varsity intercollegiate program in at least eight of the 17 sports in which the Association sponsors a championship or draws the playing rules. (Note: In administering this requirement, indoor track and outdoor track shall be considered one sport).” Additionally, 50 percent of Division I competitions should be against other Division I institutions. Division II members, by contrast, need only sponsor four varsity sports, with at least one sport in each season.

Part Two of the series ran two weeks later in the November 1 issue of the NCAA News, below a double-stacked bold headline emphasizing more important association news, “NCAA Withdraws from USOC; Calls for Congressional Action.” That saga, too, is a story for another day.

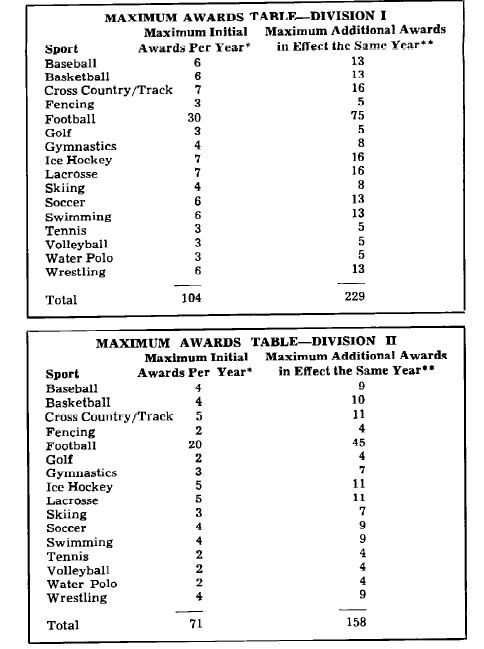

The topic of Part Two was financial aid “in which the recipient’s athletic ability was considered in some degree in determining the award.” All other aid was referred to as “financial assistance.” The proposal placed limitations on the maximum amount of permissible aid per “student-athlete” as well as maximum number of awards an institution could provide, by division.

The third and final part of the series ran two weeks later, in the November 15 NCAA News, and focused on a candidate’s procedure for accepting offers of aid. A prominent provision of this was that no offers of aid could be presented “to a prospective student-athlete prior to the opening day of classes in his senior year in high school.”

As with previous articles, this issue of the News also included a member Q&A which highlighted the following question:

There it was. A formal appeal from an unidentified small liberal arts college for a third NCAA division, met with resistance by the NCAA Council, months before the January 1973 convention to vote on the proposal. To this point, the language of the articles had emphasized only two divisions. NCAA Executive Director Walter Byers chose to ignore the discussion around Divisions in his 1995 memoir, Unsportsmanlike Conduct: Exploiting College Athletes.

Wire service stories on January 12, 1973 foretold the coming storm inside the ballroom at Chicago’s Palmer House hotel. Newspaper headlines that morning positioned that day’s debate as a “power play,” “big noise,” and “set for battle.” Associated Press reporter Jerry Liska wrote, “The large schools long have felt the NCAA’s overall policy has been controlled by smaller schools forcing their will on athletic scholarship administration and eligibility rules.”

Liska also presented the sentiment that “opponents fear it would weaken NCAA solidarity and bring eventual harmful effects on small college athletic programs.” This was being positioned as the typical scrappy little guy v. the big bully narrative.

An unidentified “prominent conference commissioner said the outcome would make or break what he considered a most significant conclave under pressure of spiraling athletic costs.” That commissioner was certainly on to something.

Ultimately, the proposed legislation failed not only to receive the two-thirds majority vote needed for passage, it did not even get a simple majority with 224 voting against and 218 voting in favor. The Little Shop on the Corner had defeated Fox Books.

Buck Turnbull, the longtime college sports reporter for the Des Moines Register, summarized the day’s events in his article under a sensationalistic banner headline, “It was the small colleges against the major universities here Friday and, as expected, Big Brother took a sound whipping at the bargaining table of collegiate sports.

“Most major universities and conferences (each conference gets one vote, too) are pushing for reorganization, and there has been talk they may eventually pull out of the NCAA unless their wishes are met.”

Turnbull quoted Russ Smith of Massachusetts Institute of Technology and president of the 234-institution Eastern Collegiate Athletic Conference, the largest voting bloc in the NCAA. “One aim of the NCAA membership for reorganization provides for self-determination - each school choosing which division it wants to belong to. We already have this now in the NCAA - University Division and College Division,” Smith said. “We simply do not believe the plan presented at this meeting provides for proper self-determination.”

While the Division split failed, the membership did agree to athletic scholarships for football totalling 30 initial scholarships per year, with 75 additional subsequent awards. It was clear that a line was being drawn to separate the schools with resources and big-time aspirations from those that did not have the same emphases.

In an effort to find a resolution, the Council exercised its bylaw power in calling for a special convention in early August. Ed Sherman, athletic director at Muskingum College in Ohio, was appointed chair of the 1973 Special Committee on Reorganization. The new committee acted quickly, proposing three Divisions. This version of the legislation would be presented to the Council in late April with voting to occur at the August meeting.

Sherman, the committee’s new chair, said in the February 15, 1973 NCAA News, “We believe our proposal will enable each NCAA member to seek the level of competition it desires and it will permit each division, within certain limits, to determine its own legislative destiny.”

Among the provisions in the final, revised proposal approved by the Council in late April was the ability for each division to adopt more restrictive legislation without the approval of the other divisions. In addition, member institutions were permitted to choose a division based on its own self-determination process, except for the 126 schools classified as “major” by the Football Statistics and Classification Committee. Any institution choosing Division II or Division III could elect to participate in Division I in one sport, other than football or basketball. It also called for representation on the NCAA Council to be divided with eight members from Division I while the other two divisions each received three members. The Executive Committee would be made up of five representatives from Division I and three each from Divisions II and III.

Finally, while the divisions would share one common set of bylaws, each division would be permitted to adopt amendments without approval from any other division, unless two-thirds of the NCAA meeting in a unicameral session objected to it.

The “historic reorganization” vote, according to an Associated Press story that ran August 7, 1973, the day after the vote, occurred at the first special convention in the 67-year history of the NCAA. Members voted overwhelmingly, 366 to 13, to support the split into Divisions I, II and III.

“The approval of reorganization will make the NCAA an even more viable force in intercollegiate athletics, said NCAA President Alan J. Chapman, a Rice University engineering professor. Chapman’s language, no doubt, was strategic as the NCAA was vehemently opposed to Senate Bill 2365, the proposed legislation which precipitated banner headline on the front page of the August 15 NCAA News. The inside pages of that same issue included leading headlines such as “Senate Bill Would Dismantle School, College Programs” and “Multi-Headed Federal Bureaucracy: Unneeded Offspring of Senate Bill.”

In 1981 on its diamond anniversary, the NCAA self-published its autobiography, a historical review written by Jack Falla titled, NCAA: The Voice of College Sports. With the benefit of nearly a decade of hindsight, Falla writes several pages, celebrating the success of the reorganization legislation, something Byers did not do 15 years later. Falla quotes Sherman regarding the labeling of divisions, “The committee started out by suggesting maybe we could call (the divisions) by colors or names to try to avoid the one, two, three implication; but as we progressed, the discussion always got back to designating them one, two and three” (p. 232).

As institutions self-selected which division to join, the final distribution, according to Falla, fell like this: 237 chose Division I, 194 chose Division II, and 233 chose Division III.

College athletics today feels more divided than ever. Small schools are struggling to remain financially solvent even as they sponsor more sports. Large schools are using their fan bases as collateral to find the biggest conference revenue deal they can while not expanding sports sponsorship. NIL deals create a marketplace for student-athletes while universities push back on the idea that these individuals are employees.

It is difficult to evaluate these issues and consider where college athletics is headed in 2023 without reflecting on the discussions that dominated 1973. In many ways, the past 50 years have taught us nothing about how administrators view college sports.There is still much - pardon the pun - division in how the NCAA structures itself. Perhaps the color idea should be brought back as it is easy to conceive Division I as the Black and Blue Division.