Can't watch ESPN right now? What you need to know about sport programming as a public good

Just don't ask Congress to intervene

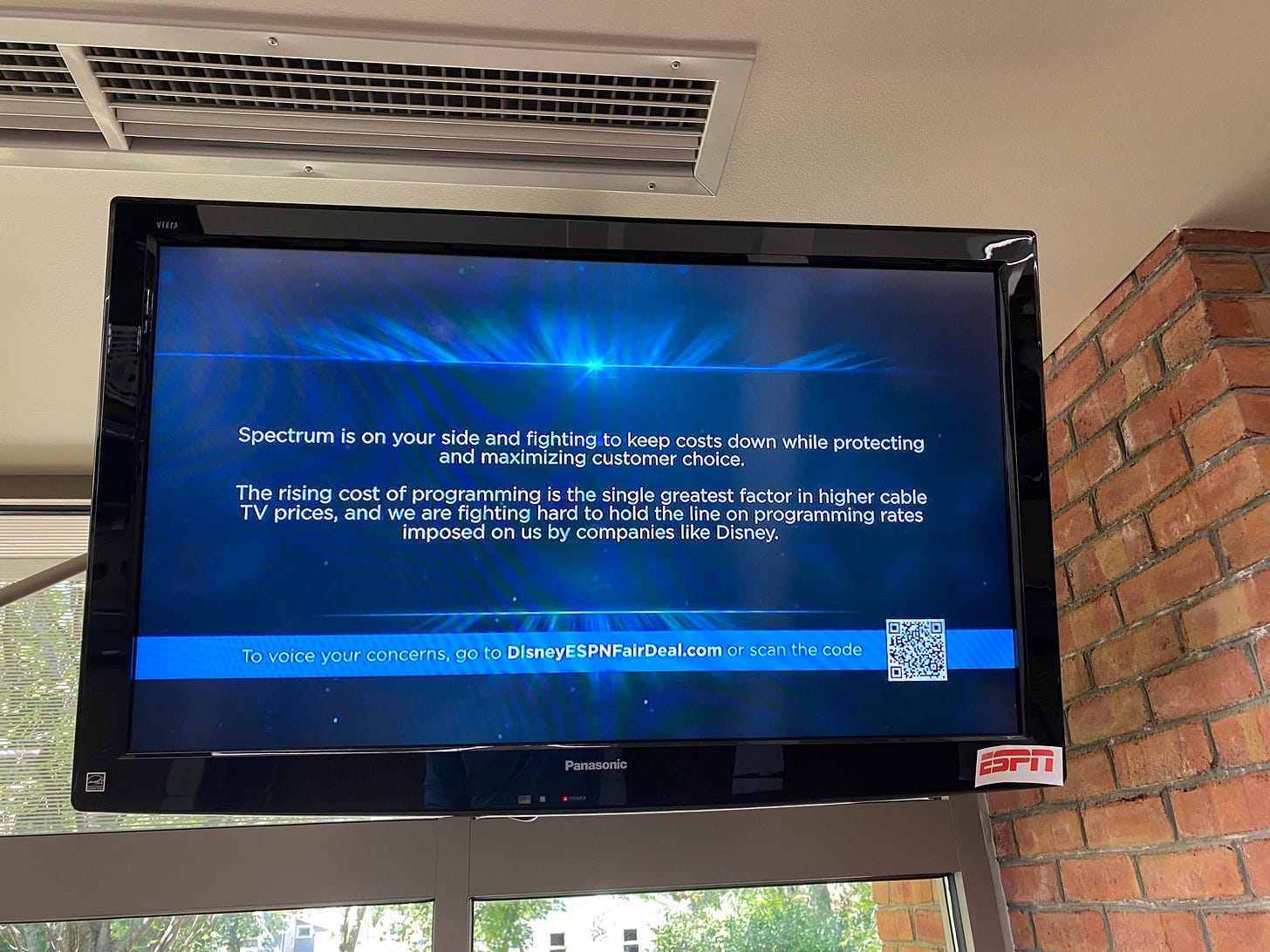

This message greeted me as I assumed my place on an exercise machine in our campus recreation center today. That we had not bothered to change the channel was both amusing and practical. The current Disney-Spectrum kerfuffle will be resolved soon. Carriage disputes such as these always are.

Why these blackouts occur is a uniquely American thing. We are one of the few countries in the world that does not treat sport programming as a public good by passing anti-siphoning legislation to prevent certain events from migrating away from free-to-air television. The rationale behind that decision is not for lack of discussion. Congress has regularly held hearings on the topic of sports programming and pay television - 14, in fact, between 1973 and 2014. But, Congress never acts.

This topic fascinated me enough to research and author a chapter on this very subject for the 2019 edited volume, ESPN and the Changing Sports Media Landscape. Here is what I concluded:

“By electing not to declare sports programming a public good and enact legislation to prevent siphoning of sports content from free television to pay television, significant migration has occurred. This fact was acknowledged not only on multiple occasions by politicians, but also by the FCC in 2012 in its annual assessment of competition in the marketplace. While this migration has led to increased league and team revenues, the negative byproducts of this migration include rising consumer costs and increasing conflicts among networks, MVPDs, and the leagues themselves.” (p. 17)

In other words, while those who license valuable property rights (NFL, U.S. Open tennis, college football) benefit financially, consumers often pay the price. Networks that often overpay for the rights to broadcast that programming, need to recover costs by raising subscriber fees. Multi-video program distributors (MVPDs), such as Spectrum, position this increase in fees to their customers as an attempt by the network, such as ESPN and Disney, to extract more money from consumers. Property owners get caught in the middle, trying to support their rightsholding partner while not alienating consumers and MVPDs.

For a long time, MVPDs had a monopoly in a given market. And while alternative providers exist, including vMVPDs Hulu (Disney-owned) and YouTube as well as satellite companies Directv and Dish, those have limitations. They need a high speed internet connection or an unobstructed view of the southern sky. So, cable monopolies and carriage disputes persist.

Sports programming is the perfect football (pun intended) to be tossed around in these debates. Rarely are people worked up about missing programming such as The Masked Singer the way they are about sports. In the era of simultaneous content production and consumption, sports remains among the few must-see content. No one wants to DVR live sports. This is particularly true as more states legalize sports betting, as Kentucky is doing this week.

Why should sports programming be a public good? One obvious factor is that the public supports most sports through tax incentives for facilities and other public subsidies. In my chapter, I cite Gaustad (2000),

“(a) the time-sensitive nature of the product; (b) the unique nature of the product, which makes it hard substitute with other forms of programming; and (c) the strong cultural connection to sport programming” (p. 5)

It is that last point that is most relevant. The basic economic definition of a public good necessitates that one person’s consumption of the product does not prevent others from consuming it. In fact, it is the social, cultural consumption of sport that we enjoy. And when billion-dollar companies bicker in public with other billion-dollar companies, consumers are harmed by not being able to share that communal experience.

But don’t worry. ESPN will be back on Spectrum soon. They always settle.